After her uncle’s death, Chloé Aïcha Boro returned to her homeland in Burkina Faso to find that the long years she spent abroad had changed the place and the people.

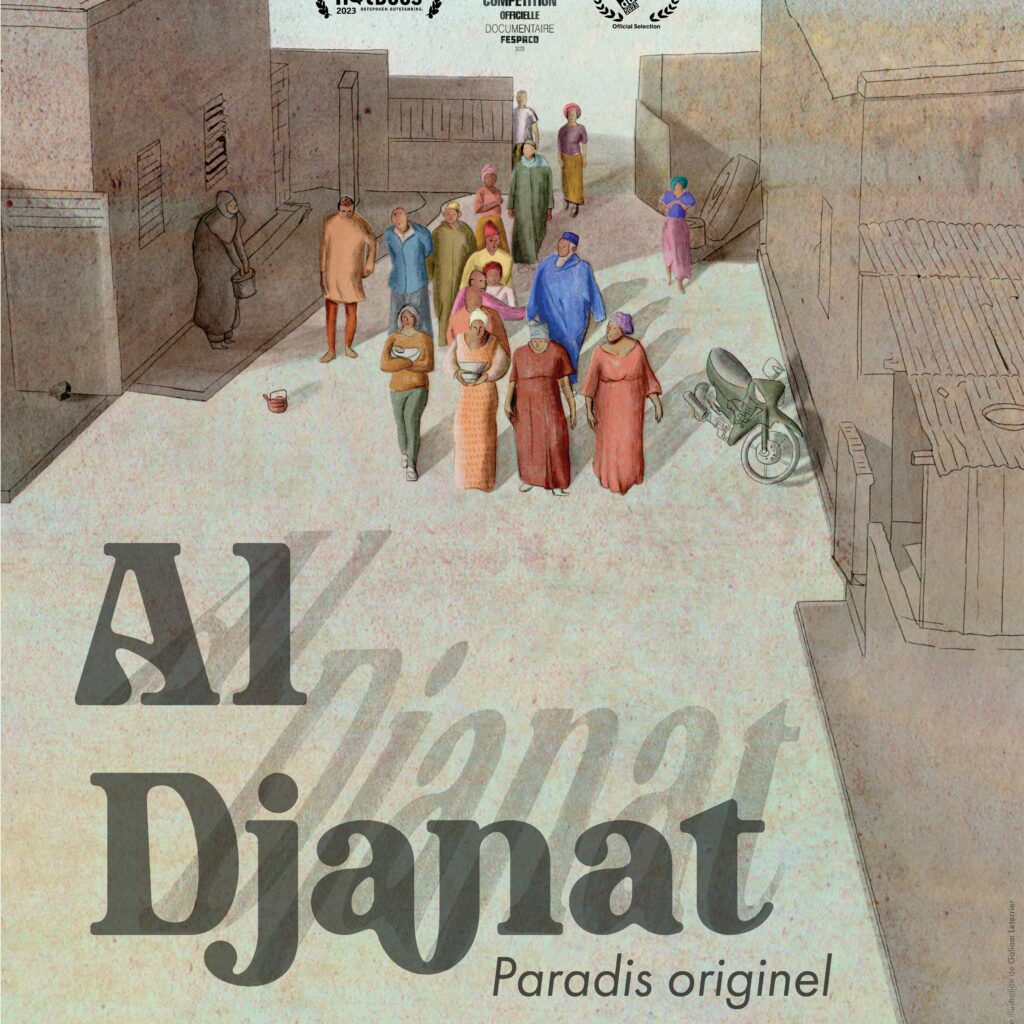

In her documentary Al Djanat, the Original Paradise, Chloé Aïcha Boro is delving into the life of her family members, while they dispute the property of the deceased uncle. The film is a joint production between France, Burkina Faso and Benin.

Uncle Ousmane, who died while performing hajj in Mecca, had 22 sons and a housing complex with a courtyard, where people used to pray (perform Islamic prayer) in it when there were only a few mosques in the area. This courtyard is the subject of dispute between the family members as some want to sell it to get their share of the inheritance and some others believe that it is the ancestral land which they cannot sell because they are deeply connected to it. But, because they didn’t teach a solution, they took their dispute to the court.

“My family is the size of a tribe”. That’s how Boro described her family in her documentary. With her camera, she engaged us in the regular debates between the family members on the regulations of Islam regarding inheritance and their arguing that women should “not get” or “just get” a small share of the inheritance.

In one of the scenes, Boro presented Sanaa, Ousmane’s daughter, who lives in the courtyard and has no other place to go if her brothers sold it. Boro, then, compares Sanaa to herself saying in her narration: “Sanaa, who I used to share with the sleeping mat. She is like a mirror to me, the woman I could have become, had I not left”. Sanaa is very nervous about the land dispute; therefore, she asked a fortune teller what will happen. “I will not lie to you, you will not keep the courtyard,” the fortune teller said.

In her documentary, Boro was keen to show the core of her society, their traditions, rituals, faith and way of thinking.

The director introduced her family’s special tradition of burying the umbilical cord. When a woman gave birth, the female family members took the umbilical cord to bury it in their courtyard as a tradition for each member of the family.

Here, the director made a comparison between herself now and her family’s tradition. She remembers eight years ago when she gave birth to her son in a French clinic. She asked them why they didn’t bring her the umbilical cord, the nurse replied that they had thrown it away. However, her family still holds on to these traditions.

The director used the umbilical cord in the documentary as a symbol of the roots that ties this family to the courtyard and that’s why it’s hard for them to sell it.

Throughout the film, Boro was keen on showing more of the traditions of her community. In each event the female family members sing traditional songs with their distinguished vocal performance, which gives us a deep image of those people and what they feel.

The film is an interesting journey that features the inheritance problem in a family in an African small village in Burkina Faso, with faithful depiction of the life of those people.

Catch the film at the Encounters South African International Documentary Festival: https://encounters.co.za/

Author: Youssra el-Sharkawy

This review emanates from the Talent Press programme, an initiative of Talents Durban in collaboration with the Durban FilmMart Institute and FIPRESCI. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author (Youssra el-Sharkawy) and cannot be considered as constituting an official position of the organisers.